Mixing an album can be more challenging than working on songs individually — but it can also be the most satisfying achievement for an engineer.

In today’s age of downloads, streaming and randomised playlists, you’d be forgiven for questioning the relevance of the album format. But most artists I speak to still value it very highly, and the resurgence of vinyl as a listening format suggests that plenty of listeners still feel the same way. All of which is great, because I still regard producing albums as the pinnacle of what I do, and it gives me a huge amount of satisfaction. Happily, as I write this article, I’m about to embark on a lot of mixing work. Three albums’ worth, to be precise.

However, album production poses particular challenges for a mix engineer. It can be very difficult to estimate in advance how long it will take to mix any given song; sometimes I can knock out a good mix in a couple of hours, but sometimes, one I’d thought would be easy takes me two days to get right. That uncertainty is multiplied when you’re mixing an album of 10 or more tracks, and can make it quite daunting, even if you have plenty of mixing experience.

For me, producing an album always used to follow a similar pattern. I’d get completely engrossed in the first song or two, and invest a lot of emotional energy in getting them sounding as good as I could, often taking a few days to do so. I’d then send the results to the artist, hoping they’d agree with my ‘vision’. Fortunately, they usually did — but at that point it would dawn on me that I now had to deliver another nine or 10 songs to the same standard! Approaching each track in the same way as the first would usually demand way more of my time than the budget allowed.

So if, like me, you rely on this sort of work to pay the bills — and especially if production budgets are, let’s say, ‘modest’ — or if you’re working to deadlines dictated by release dates, or even if you’re just frustrated that your projects never seem to end… you need to figure out how to work efficiently, while still keeping the whole process enjoyable and motivating for yourself, and of course striving to deliver the best possible end result. I’ve thought about all this a great deal in recent years, as I continue to try to improve the way I work, and in this article I’ll explain some of my own approaches that I hope you’ll also find useful.

Scoping The Job

There are several things to think about before you even get started with the mixing, and much depends on what your role was in the earlier stages of the project. My own job often includes being both tracking and mix engineer. Sometimes I’m closely involved with production decisions, and often I just wear the hat of a critical engineer who offers opinions when necessary. But in none of these scenarios can I blame anyone but myself for any problems with the technical side of the recording!

If it’s an album you didn’t record and you’re tasked solely with mixing, which is something I also do on occasion, you might be tempted simply to dive in and see where you can take things. But before you wander too far down that road you really must check that the recordings are actually mix-ready. The material needs to be of a standard that allows you to mix it to your own satisfaction and that of your client, within the time allowed by the artist or label’s budget. There’s a vast difference between the time it takes to mix an album and the time required to do lots of editing and vocal tuning to knock a session into a mixable shape. You need to be honest with yourself and the band about this, and to make the call as early as possible: if you end up rushing things and delivering substandard mixes simply because you spend all your time salvaging the recordings then, unfair as it may seem, you’ll end up acquiring a reputation for delivering poor mixes! As a minimum, then, it’s essential that you take the time to listen, in a reasonable amount of detail, to each and every song that you’re agreeing to mix.

If you feel the tracks aren’t ready, it may be that you have to suggest that the project isn’t quite ready for mixing yet, and give pointers on what needs doing, or it might be that you request a budget increase to cover the extra time involved in doing the work yourself. If you’re at all unsure, it can often be a good idea if you agree to do a trial mix first, as it’s crucial for you and the artist that the project is a good fit all round. Be wary of working for free, though; personally, I’d agree a fee for the test song, and if I was then asked to do the full album, I’d deduct that amount from the total price for the album.

All By Myself

This article assumes that the mixing sessions are unattended — by which I mean you work alone, without the artist or band present. It’s common practice and is how I prefer to work, but it’s still a good idea to be clear about this with your client before you start, and all the more so if you’re working with artists who lack experience of making records. Although the process is varies from project to project, typically I’ll suggest to a client that I get the ball rolling and that we then spend some time together during which they can offer feedback before I take things further. I might also offer the option of a final attended touch-up session if needed. You do need to be wary of the effects of ‘mixing by committee’, though; it’s always tricky and sometimes impossible to accommodate everyone’s views (even now I’m sometimes guilty of making the wrong calls here!).

It’s also important that you establish and agree a realistic timescale, and arrange how any payment will be structured. I’ve had some projects turn a bit sour simply because it’s taken longer than expected to finish the mixes to a quality I was happy with; even if we producers consider what we do to be an art form, some of our clients have different priorities, and you must respect that. I won’t go into any detail here about contracts and written agreements, but if there’s money changing hands, I’d suggest as a bare minimum that you send artist and label a clear email outlining a basic agreement.

If a mix project is likely to take place over an extended period of time, it can be good to agree staged payments. I certainly like to do this now when I’m both recording and mixing an album, agreeing sensible points such as one-third and two-thirds of the way through, with a final payment on completion. I’d treat a test mix (as mentioned above) as one of these stages, with its own payment. Working this way gives you a little extra motivation to keep things moving, and helps with cash flow if you have bills to pay. Especially if you’re working with a new client, it’s sensible to not release final high-resolution mix files before you receive full payment.

Housekeeping

It’s not the most exciting thing in the world, but one thing that will help you mix an album — whether it was recorded by you or by another engineer — is to start by paying attention to file management. If you recorded the album, it’s tempting to start with the DAW project that contains all the files from the tracking sessions, including multiple takes and so on. If you work on these, though, the folders can get large and unwieldy very quickly, so consider creating dedicated mix projects and folders that contain only the final comps and edits; most DAWs make doing this fairly painless. Having a project folder that’s 5-10 GB in size rather than 60GB will not only make it a hell of a lot easier to move between different setups if you need to do that, but it also makes it much quicker to back things up on a daily basis, which is essential. It also means the final project will be of a manageable size to archive once you’re finished. If you’re receiving the files as a dedicated mix engineer this should be less of an issue but, especially if you’re working at a non-professional level, you can’t guarantee that; as I mentioned earlier, it always pays to get a handle on the overall state of the project early on.

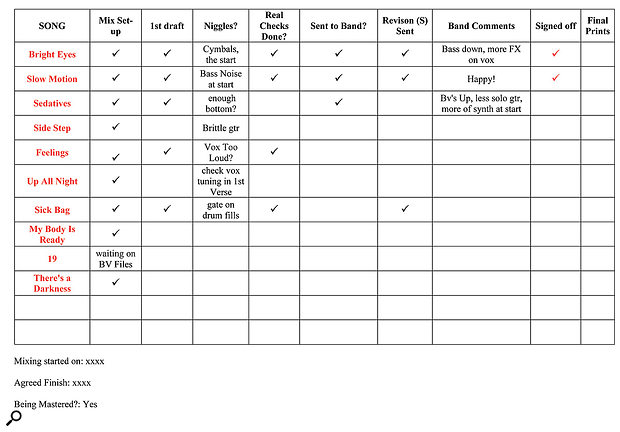

Another non-creative thing I now always do is create a basic spreadsheet or Word document, which I’ll then use to keep track of everything and to organise the different stages of the mix project. You could take this idea further, but as a minimum this would comprise a list of all the songs, along with a few notes about where I’m at with each one. I’ve recently taken to keeping more detailed notes, particularly when I start getting feedback and doing revisions on more than a few songs at a time. I find that doing this frees my mind up, enabling me to focus on the most important aspects of the mix.

One of the simple Word documents I use to plan and keep track when mixing an album.

One of the simple Word documents I use to plan and keep track when mixing an album.

Getting Started

When it comes to actually mixing, I try to ensure that I don’t burn myself out on the first couple of songs, and my approach in the early stages is designed to help with that. A typical starting place is to start work on one song that I think is generally a good representation of the whole project. I’ll start this mix with a basic mix template that I’ve set up in Pro Tools. Obviously, every engineer will have different ideas of what a template should include, and I don’t go as far as some do. However, after quite a bit of experimentation I’ve arrived at a basic template with a level of detail that speeds things up without constraining me, or making it feel as though I’m mixing by numbers. It involves a mix-bus chain and routing system, six or seven effects options set up and ready to go on Aux channels, group busses for various instruments with some plug-in options in place, and a basic set of VCA faders ready for me to assign as needed. The idea is that I can get a project up and running quickly. It minimises the time spent on administrative chores such as creating tracks and setting up routing, and it frees me to concentrate on the music for those vital few first passes through. Yet it still leaves plenty of room to flesh out the sessions as I begin to mix the first few songs.

I start with a basic mix template, but develop it for the wider project while working on the first few songs.As my first mix progresses, I’ll often use the session to create a more sophisticated template for use on other songs in the project. While every song will have its own unique requirements, there’s usually some commonality too; particularly if one engineer has recorded the project over a few sessions, there will be plenty of transferable settings for every song. For example, if a live drum kit is used, that will naturally be quite a major element in the mix. If the same drum kit was recorded in the same room, with the same mics and mic techniques, then the phase relationships between the different mics should be broadly the same, and the fundamental tone of each drum will likely be quite consistent for at least a some of the songs. It can be a similar scenario for guitars and, to a lesser extent, vocals too.

I start with a basic mix template, but develop it for the wider project while working on the first few songs.As my first mix progresses, I’ll often use the session to create a more sophisticated template for use on other songs in the project. While every song will have its own unique requirements, there’s usually some commonality too; particularly if one engineer has recorded the project over a few sessions, there will be plenty of transferable settings for every song. For example, if a live drum kit is used, that will naturally be quite a major element in the mix. If the same drum kit was recorded in the same room, with the same mics and mic techniques, then the phase relationships between the different mics should be broadly the same, and the fundamental tone of each drum will likely be quite consistent for at least a some of the songs. It can be a similar scenario for guitars and, to a lesser extent, vocals too.

Once I have, say, two songs nearly finished and am feeling confident, I like to get every other song on the album to a fairly advanced starting place by using my more developed template. I’ll also start to add a few notes to my spreadsheet and begin to develop my view of the album as a whole.

Sounds Like A Plan

Let’s assume I’ve scheduled a 5-6 hour session to work on mixing a band’s album. What would I fill those hours with? Well, I tend do my best creative work in the first few hours of a session (don’t we all?). While a big-name mix engineer, with the luxury of an assistant to do all the setting up, would often be starting a mix at this point, my aim is to get each song’s mix project to a stage where I can come in fresh next time and finish the mix in an hour or two. I’d probably spend the first few hours working on the two songs I’d chosen to start with while my ears were fresh, and then email MP3 bounces of these to myself to listen to at home or in the car.

For the rest of that session, I’d spend around 30 minutes each on other songs, building things up and tweaking the template to suit each specific song. This way, I am making good use of those later hours in the session, when I know my creative flow is on the wane. It also limits my exposure to each individual song, reducing the chances that I’ll have tired of any of them before I come to mix them.

First Impressions

I was joking the other day with another engineer about how great mixing would be if it weren’t for the artist also having to like what you do. While the words were said in jest, there was a serious point behind them: it feels good when you start to get a handle on a large project, and that it’s all coming under your control, but there’s a risk inherent in our insular way of working today, which is that you forget to check at a sufficiently early stage that your client is on board. There’s no point doing loads of work establishing a direction for the project, without first checking that it’s where the artist wants the project to go! You also need to make sure you don’t become so obsessed with one song that you leave too little time for the rest, as I alluded to earlier.

However, the other side of the coin is that sending things to your client too early on can also be counter-productive, because it’s crucial that the first mix they hear is genuinely representative of where you plan on taking things (especially if it’s the first time you’ve worked with them). So what do you do?

I find it’s helpful to seek feedback initially on more than one song, as this can give a much better representation of your thinking. For instance, the artist might come back with comments like “We really like the balance in song one,” or “There’s a bit too much vocal reverb on song two compared with the other one.” This sort of information gives you a good, clear steer, to inform both changes to these songs and the shape of the rest of the album.

Whether or not you’re mixing a full album, it’s worth considering how to increase your chances of delivering a good impression with these first mixes. If you’re mixing remotely and emailing files to your client, you have no control over what playback device or environment your client will use to audition that critical first mix. So while I’m fairly settled in my current mix space and know I can get good results in it, I still make a point of listening to at least the first few tracks of a project on a range of systems outside of the studio.

There’s a lot riding on the early bounces you share with the artists — and they could be listening on any system anywhere. So, while it’s always useful to have different monitoring options in the studio (such as the Auratone speakers, or the Sonarworks software pictured) it’s also a good idea to check on other systems in other listening environments, when you’re in a different frame of mind. Car stereos and even tiny phone speakers and earbuds can all come in to play.

There’s a lot riding on the early bounces you share with the artists — and they could be listening on any system anywhere. So, while it’s always useful to have different monitoring options in the studio (such as the Auratone speakers, or the Sonarworks software pictured) it’s also a good idea to check on other systems in other listening environments, when you’re in a different frame of mind. Car stereos and even tiny phone speakers and earbuds can all come in to play.

My little routine involves listening in my car, on a small stereo at home and on headphones. I also care and check what a mix sounds like on my phone’s tiny in-built speaker. Why? Well, you’re not mixing for the phone, but simply accepting it as the harsh reality of where your mix might end up in the first instance. Importantly, you’re also checking for possible issues that require investigation back in the studio. Phones can be quite revealing in this respect; although my phone’s one tiny speaker has a very narrow frequency response, a mix with a good vocal balance, good mono compatibility and enough weight in the upper-bass/low-mid region should still sound relatively respectable. The song should still work even on such a heavily compromised playback system, and if a vocal is way too loud or stereo elements are dramatically reduced in the balance, that’s not a good sign. Having a single Auratone-style speaker as part of your monitoring setup can be a good way to head off such issues, and there are some clever plug-ins available that try to simulate the same effect. But I suspect that just as important as hearing your work on different playback systems is hearing it in a different environment and judging it in a less critical way when you’re in a different frame of mind. Phone and car-stereo checks force a new perspective upon me, and I find this process even more revealing when I allow some time after leaving the studio before listening. For this reason I’ll generally leave the mixes overnight and, ideally, listen just before I head back to the studio, as this allows me to act on any observations almost immediately.

My little routine involves listening in my car, on a small stereo at home and on headphones. I also care and check what a mix sounds like on my phone’s tiny in-built speaker. Why? Well, you’re not mixing for the phone, but simply accepting it as the harsh reality of where your mix might end up in the first instance. Importantly, you’re also checking for possible issues that require investigation back in the studio. Phones can be quite revealing in this respect; although my phone’s one tiny speaker has a very narrow frequency response, a mix with a good vocal balance, good mono compatibility and enough weight in the upper-bass/low-mid region should still sound relatively respectable. The song should still work even on such a heavily compromised playback system, and if a vocal is way too loud or stereo elements are dramatically reduced in the balance, that’s not a good sign. Having a single Auratone-style speaker as part of your monitoring setup can be a good way to head off such issues, and there are some clever plug-ins available that try to simulate the same effect. But I suspect that just as important as hearing your work on different playback systems is hearing it in a different environment and judging it in a less critical way when you’re in a different frame of mind. Phone and car-stereo checks force a new perspective upon me, and I find this process even more revealing when I allow some time after leaving the studio before listening. For this reason I’ll generally leave the mixes overnight and, ideally, listen just before I head back to the studio, as this allows me to act on any observations almost immediately.

At the start of any mix session, I’ll also prepare a little selection of reference tracks to use. Ideally, I’ll do this with some input from the band or artist, and include at least one track that they feel is relevant. I use Sample Magic’s very handy Magic AB plug-in for this. You can do this without a dedicated plug-in, of course, but this way I can easily create a preset to insert on each song project’s master bus. When I have the first few tracks mixed, and the band is happy, I’ll also put these mixes into the preset, allowing me to check quickly how a current mix compares with previous ones.

The reference tracks are a great way of calibrating your ears; checking both technical elements and artistic decisions against material that we trust sounds good, whether in the studio or out in the ‘real world’. After more than a few hours mixing, for example, I find myself beginning to add too much top end as my ears start to get tired; a quick listen to a few familiar tracks, and I’ll know straight away if I’ve gone too far. I also get a little self-conscious sometimes about overdoing effects such as reverb or delay, and it can be reassuring to hear just how generous some commercial tracks are with them. Solid reference material is especially important for anyone working in a less-than-stellar room, particularly if there’s no acoustic treatment that targets the low-frequency response.

The Magic AB plug-in by Sample Magic makes checking your mix against reference material quick and easy. Such plug-ins can be very helpful when working across several mixes at once.

The Magic AB plug-in by Sample Magic makes checking your mix against reference material quick and easy. Such plug-ins can be very helpful when working across several mixes at once.

Troubleshooting

In an ideal world, you’d mix the first few songs, the band would love them and, fuelled by the confidence that you’re the most gifted mixer of your generation, you’d power through the rest of the album. It’s nice to dream… As with so many things in life, though, other people’s expectations can differ wildly from our own. Remember what I said earlier — that you must figure out as early as possible how you’re going to bring your project to fruition? That applies here. If you’re met with a less than enthusiastic response to the first few tracks, it’s important that you figure out why, but that’s not always as easy as it sounds. Dealing with feedback from a single artist is usually fairly straightforward, but when it comes to bands, whose members don’t always agree, nothing surprises me any more! It’s also worth noting that it’s not in some people’s nature to dish out praise; you may just get brief exchanges suggesting a few changes in level.

Your method of communication is worth considering. Email might seem an obvious choice, as it allows you both to get all your thoughts down systematically. Equally, though, it can often make it difficult to gauge strength of feeling, and what’s really driving feedback. If you sense alarm bells ringing, I suggest you just pick up the phone, so you can ease any concerns or root out a problem, but do approach your conversation in the right frame of mind; don’t go in too defensively or portray any insecurity in your ability, but do check in to make sure everyone is happy and try to eliminate any doubt in your mind. That’s important, as any such lingering doubts make it very hard to mix the remaining songs. If things get a bit rocky — and from time to time they will — you just have to remind yourself that what we do is highly subjective, and that being pushed and challenged, though uncomfortable, invariably makes us improve. You must try and work with whatever feedback you’re given, but it’s important that you also retain confidence in your ability. In terms of practical suggestions, extra reference tracks may be helpful, or you might get the client to take a bit more ownership by bringing them in to the studio, or perhaps chatting over Skype.

Moving Forward

OK. Let’s assume that you’ve got over the initial feedback hurdles, and things are now going well. You have the band/artist on side and, after a few tweaks, a couple of mixes are in the bag. Things can sometimes move fast from here. Hopefully, you’re in a position to reap the benefit of all that preparatory work you did for the remaining songs, and on organising the project as a whole.

Even if you have access to a good console, consider working ‘in the box’ — the advantages of full recall allow you to work on several tracks in parallel, and make working on mix revisions much easier.

Even if you have access to a good console, consider working ‘in the box’ — the advantages of full recall allow you to work on several tracks in parallel, and make working on mix revisions much easier.

Next, I like to work on two, or possibly three songs at a time, and then get these signed off. To make this possible, you need complete recall of the sessions, which is one of the massive advantages of mixing ‘in the box’; it helps me stay fresh, and to avoid becoming bogged down in the details of one track. Once this second batch is done, before you know it you’re somewhere around halfway through the album, and sometimes further. I find that it’s fairly common for there to be one track that requires that bit more effort to mix than the others, or one that you get a bit stuck on for a while, and I’ll tend to put this to one side while I build momentum. Once I get on to the final few songs, I find I have to be particularly self-disciplined — the final touches on a mix, like level rides, and managing the finer details or effects and processing, can seem that much harder to put in place. Such details are so essential to a good mix, though, that you need to dig in!

Being A Better Finisher

One thing about mixing that’s incredibly difficult to learn is when a mix is actually ‘finished’, and this is a problem multiplied when mixing an album. If you’re an eternal tinkerer, and especially if you find yourself returning to mixes even after the client has signed them off, you can slide quickly down a very long and slippery slope. The best advice I can give is to get more mixes under your belt, preferably in a variety of genres. You develop a sense of when you’re starting to overwork a mix, and when there’s a little more to be squeezed from it by starting on version 38! There’s a quote that runs something like: “You never finish a mix, you just give up on it,” and it’s famous for a reason. It’s not a defeatist statement, but acknowledges an emotional truth about mixing: as there’s no perfect mix you’ll never be 100 percent happy with yours, so you must learn to know when it’s time to let go.

Getting a client to let go of a mix can be tougher, and many mix engineers will stipulate how many revisions they are willing to do for free as part of their original agreement. I might offer two free revisions for the price agreed, for example. This could be critical if you’re mixing outside of the box, but even when working entirely in software, your project needs to have a defined end point. I don’t tend to get too formal about this myself, but I have had projects where the amount of revisions has started to get a bit silly. One instance springs to mind where a band were driving themselves crazy trying to get the level of the bass guitar right and wanted to settle on a point where the bass player’s girlfriend thought it should be when listening in her car. This was way too loud in my own opinion, so I politely pointed out that if they really didn’t know and were happy for her rather than me to decide then we might end up having something of a trust issue!

For managing mix revisions over multiple songs, my mix spreadsheet is really helpful as it can makes it easier to keep track of things when you have a number of songs on the go. I’ll often cut and paste comments from emails straight into the spreadsheet so I can refer back to them easily. Still, there’s a solid argument for not having too many mixes ‘live’ at any point. I find it better to sign off two or three songs at once, and to be clear to the band that this is how things must work and why.

Consistency

While the level and dynamic of different tracks on the album might vary, the lead vocal (or other lead instrument) typically ends up at roughly the same overall level on every song.One question a lot of people who are inexperienced with album production seem concerned about is what degree of consistency there should be across all the different songs on the album. How important is it that an album has a consistent ‘mix’ sound throughout? Well, it depends a great deal on the nature of the material, of course, but taking the example of a band working on something like a concept album, or even a simple snapshot of where they’re at, I think it’s is an important consideration. That said, if, as an artistic statement, each song has a different sonic direction, you might deliberately work to emphasise this further — that’s one to explore up front with the artist in question, of course. Assuming you are looking for a consistent sound, the fact you’ve mixed a whole album in a relatively short time, in the same room, using similar mix tools, will mean that this sense of consistency will tend to take care of itself.

While the level and dynamic of different tracks on the album might vary, the lead vocal (or other lead instrument) typically ends up at roughly the same overall level on every song.One question a lot of people who are inexperienced with album production seem concerned about is what degree of consistency there should be across all the different songs on the album. How important is it that an album has a consistent ‘mix’ sound throughout? Well, it depends a great deal on the nature of the material, of course, but taking the example of a band working on something like a concept album, or even a simple snapshot of where they’re at, I think it’s is an important consideration. That said, if, as an artistic statement, each song has a different sonic direction, you might deliberately work to emphasise this further — that’s one to explore up front with the artist in question, of course. Assuming you are looking for a consistent sound, the fact you’ve mixed a whole album in a relatively short time, in the same room, using similar mix tools, will mean that this sense of consistency will tend to take care of itself.

One consideration when mastering will be the relative level of the different tracks, and recently I was asked how important I feel it is to have consistency in the loudness of the lead element of each track — usually the lead vocal, but sometimes it might be a solo instrument — irrespective of the overall level of the song. This is worth contemplating, as it’s not something that can really be changed during mastering without impacting on the rest of the mix. It could certainly be distracting to have wildly different lead-vocal levels from song to song, even if the level of the rest of the instrumentation varies wildly. A low vocal level on one track might make that song seem a bit wimpy, while too high a level might make another stick out in an awkward, unwanted way. There are no hard rules here, but this is one of those things you can consciously check — so think about this when asking yourself if the transition between songs is likely to work as desired. If you want to ‘check in’ and get a feel for how the songs sit with each other, it’s not a bad idea to lay the album out in a mastering-style session, even if you won’t be doing the mastering yourself. I recently started using PreSonus’s Studio One Professional for this purpose; when it comes to mastering, I found its options for creating DDP files and checking relative loudness extremely impressive.

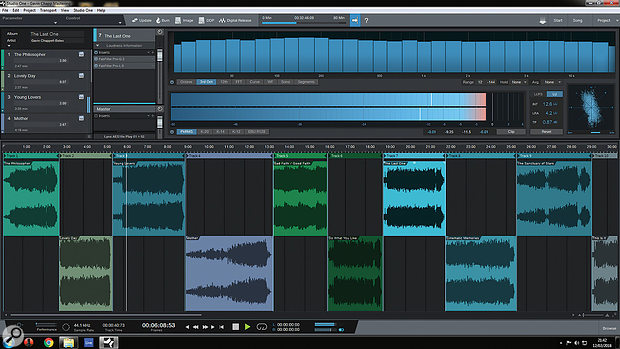

Although mastering is slightly outside the scope of this article, you still have to mix with the end result in mind. To that end, it can be helpful to arrange your mixes in a mastering-style setup, as shown here in PreSonus Studio One, playing with the order of tracks, assessing the relative levels and tonality, and so on.

Although mastering is slightly outside the scope of this article, you still have to mix with the end result in mind. To that end, it can be helpful to arrange your mixes in a mastering-style setup, as shown here in PreSonus Studio One, playing with the order of tracks, assessing the relative levels and tonality, and so on.

Summing Up

Recently, a Manic Street Preachers quotation grabbed my attention. They described making an album as “the closest a band can come to producing a piece of artwork”. I agree with this, and in order to think like an artist at the mixing stage, we need to develop a few project-mangement skills — and, even more importantly, people-management skills. Once we have these things under control, we can get our heads into the music, which is where we want to be for as much of a project as possible. Hopefully, I’ve provided a few ideas, some guidance, and some encouragement for when you’re tasked with mixing a larger group of songs. It can be hard work, but it is also extremely rewarding when you get that final track finished.